Scientific Portfolio’s Investment PhilosophyUser Solution Guide | April 2023

Introducing a portfolio analysis and construction philosophy, consistent with the academically validated principles of factor investing, and integrating finance and sustainability into an intuitive framework

The Hunt for a Suitable Equity Portfolio

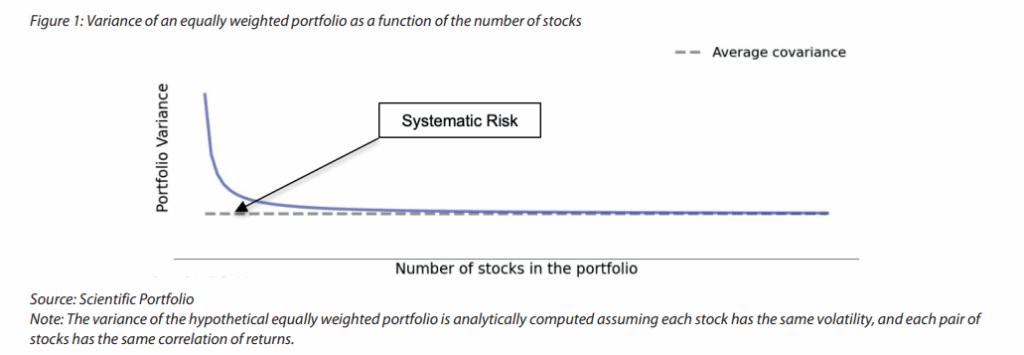

Portfolio construction is a powerful financial technology that investors can leverage to create more efficient investment opportunities in the face of uncertainty and to implement their financial and extra-financial preferences. Efficiency is largely obtained thanks to the benefits of diversification, allegedly the only free lunch in finance. However, as useful as diversification may be, it alone is not sufficient to construct a portfolio because some sources of common risk cannot be fully diversified away, as evidenced in Figure 1 for a hypothetical equity portfolio.

The level of the plateau reached in Figure 1 is, by design, the portion of equity risk that could not be entirely eliminated through diversification, also called systematic risk (as opposed to the idiosyncratic risk that is fully diversified away). It is equal to the average covariance of returns, across every stock pair in the portfolio. Understanding the source and structure of covariance (or correlation) between stocks is therefore a prerequisite to identifying and quantifying the systematic risks of equity portfolios. Additionally, investors searching for efficient investment opportunities need to also identify robust sources of long-term performance to inform their portfolio selection and allocation processes. Absent any market anomaly, the robust sources of performance should be found precisely amongst the aforementioned systematic risks, because investors require a premium for bearing those risks that cannot be fully diversified away and that hurt a portfolio mostly in bad times.

One might be tempted to select a diversified portfolio based on simple historical measures of risk and return such as past volatility, performance or Sharpe ratio. However, these metrics are heavily sample-dependent and may not persist in the future (out of sample), so a thorough analysis of the drivers of risk and return is required to form an educated view on the level of efficiency of a portfolio. Fortunately, a large body of financial research on asset pricing and factor investing is available to guide investors in their search for efficient portfolios. In line with academic literature, we consider factors as the optimal means to clearly visualize the drivers of both risk and potential long-term performance in an equity portfolio. Every systematic risk factor is characterized by its ability to explain the common variations in stock returns, but academia distinguishes between those that are expected to generate excess returns in the long run and those that are not known to attract a risk premium.

The first category is often referred to as fundamental risk factors or rewarded risk factors and they are backed by an extensive body of research that recognizes them as persistent drivers of expected returns (i.e., long term performance). Indeed, these risk factors represent sources of common risk that cannot be fully diversified away and that are compensated by a risk premium. They have been subject to a high degree of academic scrutiny and challenge, and their economic rationale has been extensively documented. As a result, investors can avoid the trap of data mining and construct portfolios that are likely to remain robust out of sample. The seven generally accepted fundamental risk factors include the Market, Value, Size, Low Risk, Investment, Profitability and Momentum.

The second category is unrewarded risk factors, because while they are deemed sources of common risk and contribute to the risk and short-term performance of a portfolio, they are not considered by the finance literature to contribute to the expected excess returns and long-term performance of the portfolio. Sector/industry factors typically fall into this second category of factors that remain important for risk management purposes. The third and final contribution to portfolio volatility is the collection of stock-specific idiosyncratic risks which are considered fully diversifiable and are naturally unrewarded.

In the absence of a particular view on the market, and provided an investor is willing to accept the risk of deviating from the broad-based cap-weighted strategy, our investment philosophy is that over the long term, well-constructed systematic investment portfolios are those that are mostly exposed to rewarded risks and that have managed to reduce most of their idiosyncratic risk thanks to diversification. To assess the extent to which a portfolio is exposed to fundamental (and thus rewarded) risk factors and whether such exposures are spread out appropriately, we use a measure called Factor Quality. Therefore, a balanced exposure to several rewarded fundamental factors results in a high Factor Quality score and enhances the potential for long term risk-adjusted returns because factors are not perfectly correlated. Indeed, while fundamental factors are expected to individually outperform on average, their outperformance does not generally occur at the same time.

When modifying or constructing a portfolio to meet a specific objective, it is therefore important to keep in mind the principle of maintaining well-diversified, rewarded factor exposures. This is especially relevant for investors wishing to pursue an extra-financial (ESG) objective while meeting financial constraints related to their fiduciary responsibility. In practice, implementing or identifying portfolios in line with these principles requires a comprehensive, yet parsimonious and actionable, risk model.

Risk Model

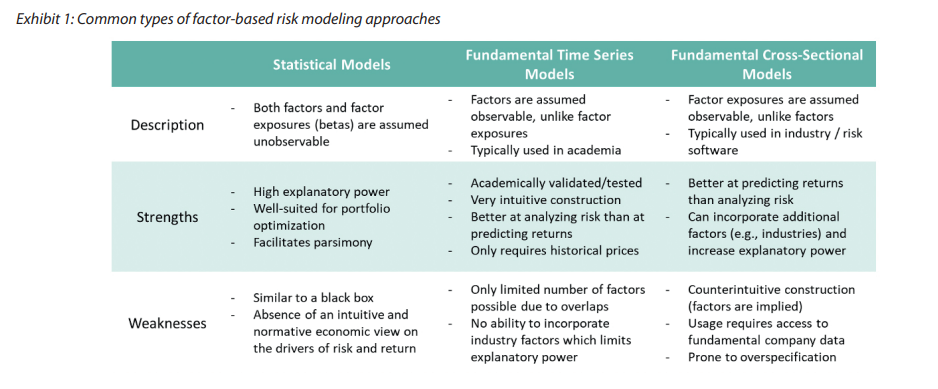

Scientific Portfolio recognizes that building a risk model is perhaps as much of an art as it is a science. There are three common types of factor models used by academics and industry practitioners: i) statistical models, where both factors and factor exposures, i.e., betas, are assumed unobservable and need to be estimated, ii) fundamental time series models which are popular with academics and where factors are assumed observable but not betas, and iii) fundamental cross-sectional models, used by popular risk engines in the industry and where betas are assumed observable but not factors. Exhibit 1 provides a more detailed description and a comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of the three approaches for designing a risk model.

Having reviewed the various approaches to factor modeling, we have designed our risk model to have the intuitive appeal of a time series approach, the flexibility of a cross-sectional approach, and the parsimony of a statistical approach, along with a very strong ability to explain risk. We first scan a portfolio through the intuitive lens of a fundamental time series model, using the seven fundamental time series factors and then, separately, the ten unrewarded sector-based risk factors1. The seventeen estimated betas (factor exposures) represent a full risk identification card that is fed into the cross-sectional engine, which in turn, appropriately disentangles the informational overlaps between fundamental betas and sector betas. However, the cross-sectional disentangling does not address the fact that there are arguably too many betas in the risk identification card, and we are likely over-specifying the model. That is why our cross-sectional engine also includes a critical feature designed to avoid over specification (in many ways similar to what Principal Component Analysis (PCA)-based statistical models do) and reduce (behind the scenes) the dimensionality of the model. This ensures there is no “double counting” and makes the model results more robust. The main output is an exhaustive decomposition of the systematic risk of the portfolio across seventeen risk contributions, each associated with an intuitive and meaningful risk dimension.

The overall architecture of our model is therefore based on a combination of standard approaches inequity risk modeling, the technical details of which are available on our platform2. The cross-sectional architecture works in tandem with the time series framework to provide transparency and flexibility without sacrificing robustness. This is achieved by reducing the dimensionality of the model while disentangling the informational overlaps. This allows our model to combine a high level of actionability (based on economically meaningful intuitive factors) and a high level of explanatory power.

ESG Investment Framework

Traditionally, once a set of financially efficient portfolios have been identified or implemented, investors would determine their optimal allocation by selecting the efficient portfolio that best aligns with their risk and return preferences or constraints. The advent of ESG investing requires enriching the traditional investment framework while staying true to academically validated principles and carefully anticipating the possible effects of ESG on financial performance, financial risk and investor preferences As far as performance is concerned, academic research currently provides no conclusive evidence of significant outperformance associated with incorporating extra-financial objectives in an investment strategy (e.g., excluding some stocks or sectors based on ethical principles). One possible explanation is that an investor getting extra-financial satisfaction from a particular ESG stock must be willing to pay slightly more for it than for a non-ESG stock offering identical ex-ante expected risk and return characteristics but carrying no extra-financial benefit: the investor is effectively prepared to “pay” for the additional satisfaction brought by the ESG stock, and therefore to accept a lower expected financial return. In other words, virtue is its own reward and investors should not expect to “do well” in the long run as a result of “doing good”. Additionally, empirical research highlights that ESG strategies that have shown outperformance in popular articles in fact had significant exposures to known sectors and factors, which explained most of the observed outperformance3. It is also worth noting that a lower ex-ante expected return is certainly not incompatible with short term market outperformance driven by external ESG shocks or shifts in taste4: while ESG concerns have increased among investors, leading to positive investment flows into ESG products and temporary outperformance, academic research shows no evidence of a long-term outperformance from high-sustainability funds compared to low-sustainability funds.

As far as risk is concerned, it is important to judge ESG through the same lens and framework as other traditional types of risk. Indeed, ESG-related issues that may have a material financial impact on an investment portfolio are simply new sources of financial risk. In this context, the question of whether ESG considerations lead to the introduction of new systematic risk factors, that is, factors that can explain the common time variations in stock returns, is still debated in academic literature. Some empirical evidence has been provided for specific dimensions of ESG (e.g., climate transition risks) but this cannot be affirmed for all ESG criteria. Even if ESG risks do not have a strong influence on the total risk of a portfolio, they can still represent a significant contingent risk that could materialize in certain adverse scenarios such as a disorderly energy transition. For this reason, institutional investors need to carefully consider the implications of proactively managing ESG risks in their portfolios with regards to their fiduciary duties. One of the approaches of Scientific Portfolio to ESG risk is to integrate it in the exact same factor-based risk framework alongside other traditional financial risks so that investors can make informed decisions.

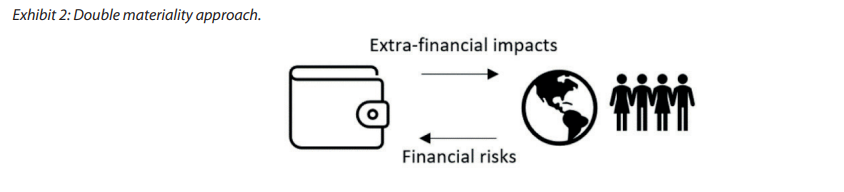

Finally, ESG issues may affect the individual preferences of investors who wish to pursue extra-financial objectives instead of, or in conjunction with, financial objectives. Portfolio construction is also a financial technology that helps investors customize their investments to their own preferences, and Scientific Portfolio offers ESG impact functionalities to investors interested in following a double materiality approach (i.e., both the new financial risks linked to ESG issues and the extra-financial impacts of finance on the environment or on society, see Exhibit 2).

Sustainable Investment Philosophy

Our ESG impact framework is consistent with the original and historical concept of sustainable development (dating back to conversations between Jefferson and Lafayette in the 18th century about the “self-evident” nature of the “rights of future generations”) which is very close to a do no harm (DNH) injunction.

Exclusion strategies are naturally associated with a DNH approach and enable investors to align their entire investment universe with the original concept of sustainable development while retaining the flexibility to rebalance or adjust weights within a portfolio. These exclusion strategies therefore ensure that a portfolio, irrespective of its allocation, does not contribute negatively to sustainable development. This approach is likely to be more robust out of sample than score-based approaches that rely on the ex-ante maximization of the portfolio’s weighted-average score (determined by aggregating the ESG scores of individual holdings). Additionally, when using scores, the negative impact of some holdings may be offset by other holdings with higher ESG scores. This could result in a positive aggregate portfolio score despite some holdings still “doing harm” and contributing negatively to sustainable development. For instance, the Great Green Investment Investigation (GGII) study revealed that nearly half of the European “super green” funds studied actually invest in fossil fuel or aviation-related assets, while another study found that only 10 per cent of ESG funds available to retail investors in Germany were free from controversial investments7. Finally, the academic literature8 has documented industry practices that consist in re-writing (past) historical ESG scores, thus calling into question the relationship between ESG scores and returns sometimes observed in the data.

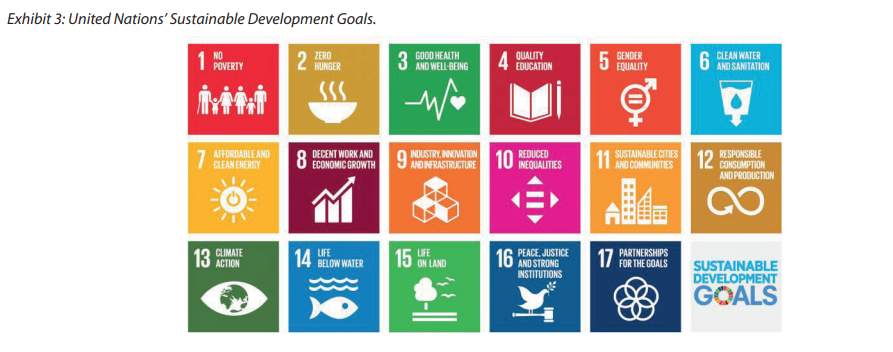

We implement our DNH philosophy by relying on a set of commonly accepted extra-financial objectives, namely the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, see Exhibit 3) announced in 2015, which are used by investors to assess and manage the contribution of their portfolio to one or several SDGs. While most of the current SDG frameworks for investors focus on the positive contributions of stocks to SDGs, Scientific Portfolio considers it a priority to identify potential negative contributions to SDGs.

Therefore, we have developed a comprehensive and objective framework that identifies a company’s activities or behaviors that might have a negative impact on each SDG and its corresponding official Targets.

Our ESG impact framework also relies on two other levers of action to pursue extra-financial objectives: reallocation and engagement. These two levers are relevant for portfolios aiming to go beyond DNH by generating a positive impact (“do good”) or more generally for the dynamic assessment (that is, not just at a single point in time) of a portfolio’s ESG impact, e.g., whether it is evolving towards or away from sustainability, or whether it is aligned with a given climate pathway.

It is worth remembering that an ESG investing framework is only as solid as the data that supports it. Unfortunately, there is no long-established standardized and mandatory reporting practice for ESG matters. The solution envisaged so far by the industry to address the data deficiencies (with respect to quantity, consistency and quality) has been to rely on commercial ESG data providers that produce aggregate “scores” or “ratings” and thus provide their expert assessment of the ESG quality of each company. Unfortunately, this has raised a number of new issues (quantity bias, non-definitive scores, halo effects, measurement-related divergence) that have been recently documented in the academic literature. More generally, it is much easier to detect an ESG issue than to identify virtuous corporate behaviors, so low scores are likely to be more reliable than high ones, a bias that advocates for the caution of a DNH approach. However, being cautious does not preclude investors from being ambitious: a strategy seeking to do no harm to any of the 17 SDGs would require excluding almost 40% of the global developed market equity investment universe. Such a massive reduction of the investment opportunity set would no doubt be deemed too extreme by some investors but also have large effects on potential risk-adjusted returns. Therefore, those investors subject to fiduciary duty will require advanced analytics that straddle finance and ESG to carefully identify and quantify the resulting trade-offs.

Conclusion

Scientific Portfolio’s equity investment philosophy aims to reconcile finance and ESG and recognizes that a double materiality approach is needed to enrich the traditional investment framework.

First, we begin with an intuitive and actionable risk model that relies on the academically validated principles of factor investing. Second, we expand the framework by introducing ESG risks, which we consider as belonging with traditional financial risks (and which can in some cases be analyzed through the same academically validated factor-based methodology). Third, we consider virtue to be its own reward: we concur with academic research that the pursuit of ESG impact is not expected to be a source of outperformance. Finally, our DNH approach to sustainable investing (and its natural implementation through screening and exclusion) is rooted in history and offers the flexibility to pursue a large variety of ESG impact objectives and ambition levels, while allowing to easily clarify the resulting financial implications for the portfolio.

Combining finance and ESG therefore leaves investors with more choices. The latter will be largely influenced by complex personal preferences which will likely make consensus-based approaches somewhat elusive. As a result, investors will require customization capabilities and transparency to construct their very own “financially-and-extra-financially-optimal” portfolios. The search for the optimal portfolio should be grounded on a comprehensive set of analytics that identify the relevant portfolio allocation actions and that help investors navigate possible finance/ESG trade-offs.

Turning our philosophy into practice entails allowing investors to pursue financial objectives subject to extra-financial constraints or to pursue extra-financial objectives subject to financial constraints. Our analytics platform is precisely designed to assist you with the definition of those objectives and constraints, and to help you fine-tune them in accordance with your appetite for customization.